exhibition home page

The Origins of the “1890”

The “1890” was the first history of the Society written for its own sake, but accounts of the origins of the Writers to the Signet had been written before, driven into existence by the exigencies of professional life. In 1731, the Society presented a Memoriall Concerning the Rise and Constitution of the Society of Writers or Clerks to His Majestie’s Signet in Scotland to the Secretaries of State (Lord Harrington had held the post jointly with the Duke of Newcastle from the previous year). The Memorial, transcribed in the “1890” and preserved in manuscript in the WS Society archives, was both an account of the Society’s history and development and a plea for reform of legal fees that no longer provided a reliable living for ordinary Writers to the Signet. In 1833, Writer to the Signet James Darling’s Practice of the Court of Session included a short but useful account of the Society which, echoed in later revisions of the work, stood as the closest thing to an official account for sixty years.

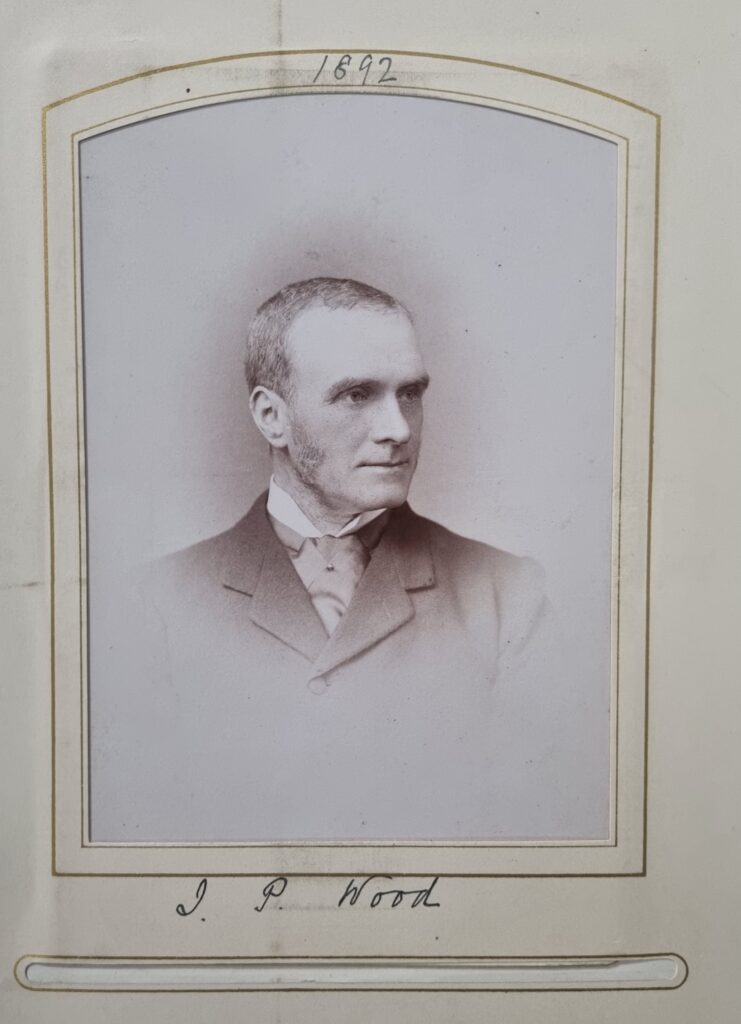

It may be that the actual “1890” itself was Signet Librarian David Laing’s idea originally. At any rate, knowing that Laing was thinking of preparing a chronological list of the members, Writer to the Signet John Philip Wood wrote to Laing on 4th Nov 1869 about the list of early Writers to the Signet that Wood had put together for his own interest. Both Laing and Wood would have been well aware of the earliest Scottish example of such a list – that of the University of Edinburgh’s famous Speculative Society, who issued it in 1845. Many members of the Spec later went on to become Writers to the Signet, and the Spec‘s publication was also the first to list biographical information of Society members to any great extent. In 1858, David Laing had been a significant driver behind the Ballantyne Club’s publication of historical Edinburgh University graduates, and in 1875 the Juridical Society (in which the WS Society was a dominating presence) produced it’s own historical members list.

The second half of the nineteenth century was the great period of historical consolidation, in which the publications of intellectual societies and the arrival of the great lexicographical and biographical dictionaries put in the groundwork for future decades of professional scholarship. Abstracts from public records would be a significant part of this, and David Laing was on the committee of the Scottish Burgh Records Society, which did for the council records of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Dundee and Stirling what the “1890” would do in the same period for the WS Society.

John Philip Wood (who shared his name with his forebear, the great Scottish historian and editor of the Scottish Peerage) was part of the Committee set up by the WS Socidety on 7th Feb 1887 to create what would become the “1890.”

The Committee consisted of the Society office holders and a remarkable set of scholars and scholar-lawyers, including:

- Charles Cook – genealogist and historian of the Dandie Dinmont Terrier

- William Traquiar Dickson – antiquarian and restorer of Saughton House

- Librarian Thomas Graves Law – authority on the religious sixteenth century and founding secretary of the Scottish History Society.

- Francis J Grant WS – then Carrick Pursuivant at the Court of the Lord Lyon, later Lord Lyon King of Arms and author of over sixty genealogical works.

Law would write the chapter on the Library and contribute heavily to the other historical sections of the book. Grant would contribute the list of members, the list of office bearers, and the index.

The work was divided into three parts:

- a basic narrative of the Society’s institutional history paying particular attention to the Society’s educational and charitable activity;

- a list of members and office bearers from the opening of the Society Sederunt Book in 1594;

- an abstract from the Sederunt Book.

The aims, the introduction declared, were to “trace the origins and progress of the profession which has given to the society its distinctive name, to describe the various duties and privileges which have accrued to the body in the course of time, and to tell the history of its funds and its library, and its connection with the university of Edinburgh and other public institutions.”

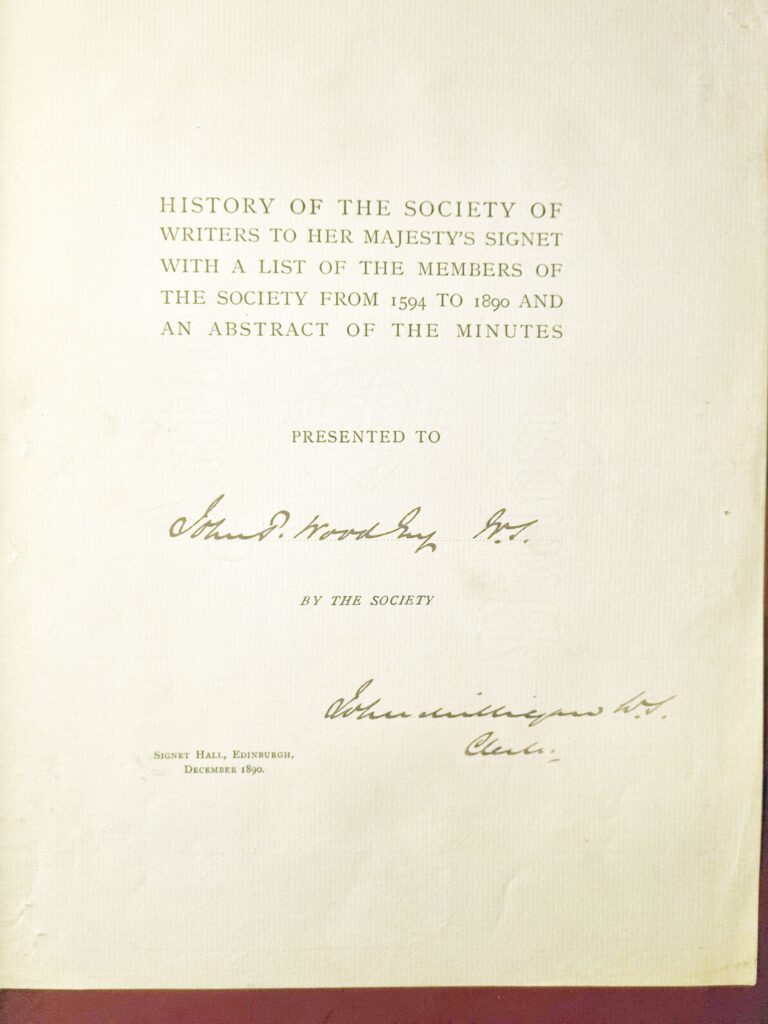

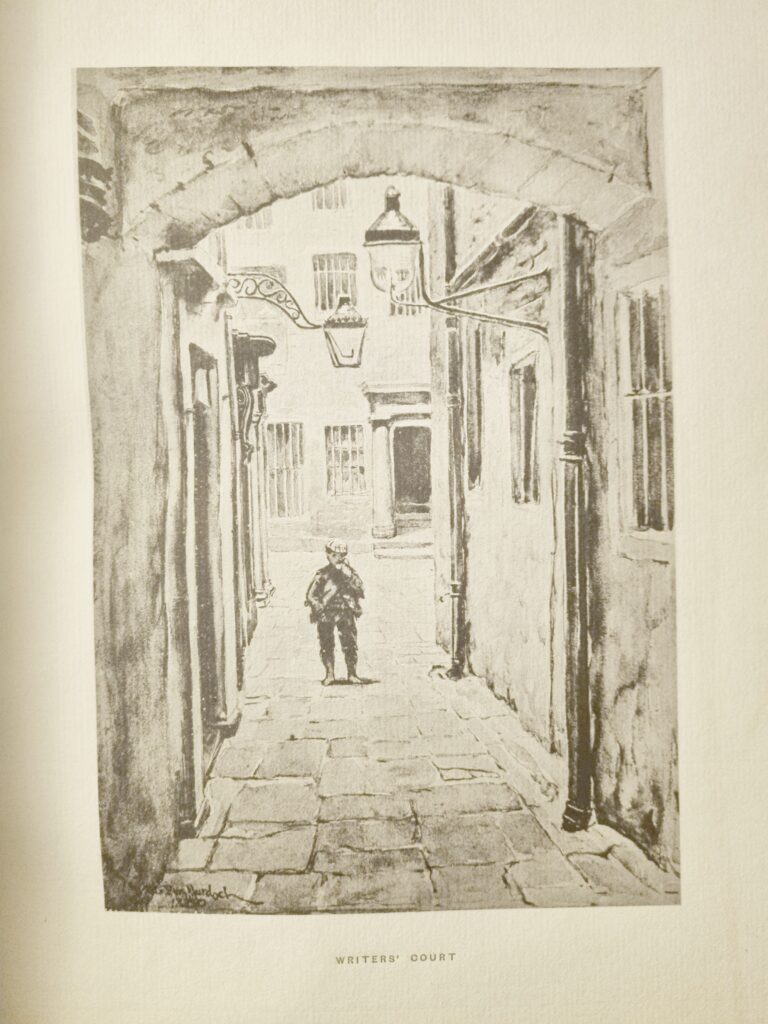

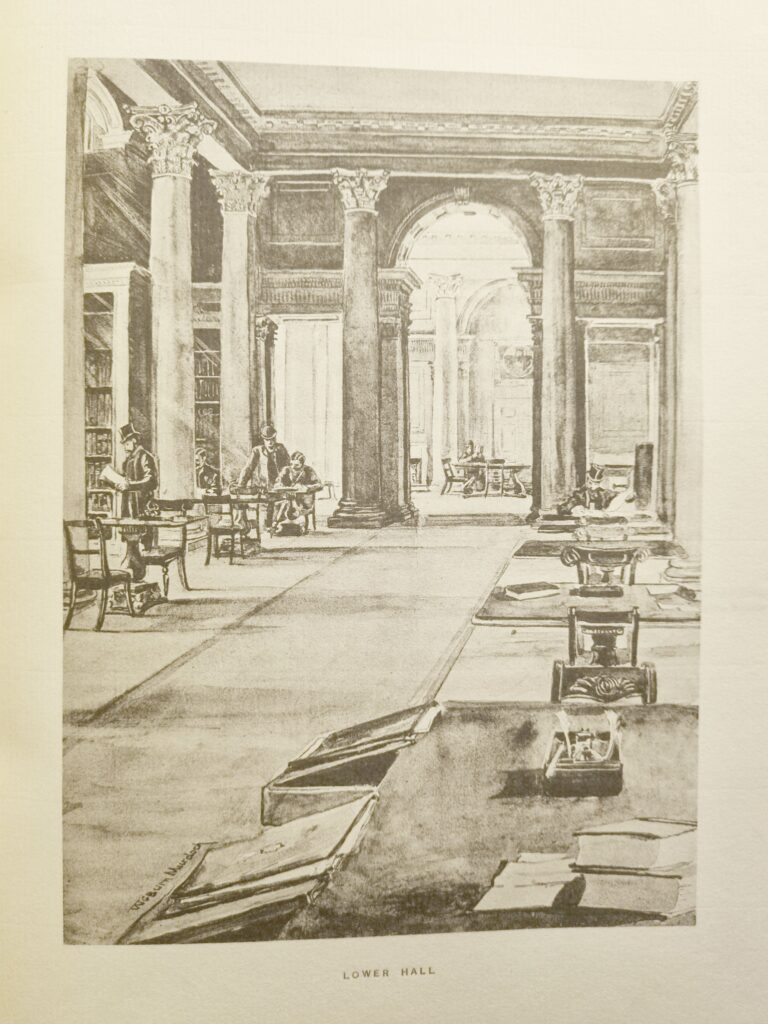

It was a lavish production, a large folio, printed on handmade paper and illustrated by watercolours by the artist William Burn Murdoch (allegedly the first man to play the bagpipes in the Antarctic). The finished book was distributed to the major libraries and intellectual societies of Britain and Europe and has long since been freely available in digitised form.

The book’s early days were not without hazard, however. The first print run included an error in the List of Members in which the wife of one living Writer to the Signet (Duncan Shaw) was given unto his alphabetical contemporary (David Shaw). The run had to be recalled and destroyed. Only one copy of the initial run, that of Keith Ramsay Maitland, is known to survive.

Soon after the book’s appearance, it was the subject of a long and mocking essay published anonymously in the Scottish Legal Review, which accused the Society of committing the sins of grandiosity and self-congratulation and which saw the whole production as inviting ridicule. But it is unfair to describe the “1890” as “history written by the victors”. The chapter on finances is all too open about the humbling that the Society had experienced in the middle of the nineteenth century and honest about how it had brought some of those troubles upon itself.

Yet the history of the Society, especially from 1722 onwards, was one that contained a remarkable sequence of unmistakeable triumphs. The Signet Library was world famous, housed in a building a visitor termed “the palace of books”; the Society founded and ran a magnificent school for orphans, John Watson’s Institution, and was one of the first institutions anywhere to boast its own pensions scheme, the Widows Fund. It had founded its own professorial chair at the University of Edinburgh. For centuries it had been, as advocate Sir Charles Shand commented in 1848, famous for “the attention which has been paid to the education, both general and professional, of their apprentices” and completion of a WS apprenticeship was long affored the popular equivalent status of a university degree. For an organisation whose membership at the time varied between 450 and 650 these are genuine achievements deserving of note and record.

The “1936”

There was talk of a new edition in 1901, to which Francis Grant WS was prepared to contribute material on the Society’s heraldry, but in May the decision was taken not to proceed. Although Grant was understandably disappointed, he would nevertheless be on hand in November 1933 (by which time he was Lord Lyon and had received his knighthood) to join the committee set up to produce a revised supplementary volume. The new committee was no less distinguished than its predecessor, with the author William Roughead WS and the great art connoisseur and collector Kenneth Sanderson WS on board. The “1936,” issued with the 1914-18 war still fresh in the memory, is illustrated by a single photograph – of the Memorial to the Society’s Great War dead (the earlist known photograph of the Lower Hall).

The “1936” is distinguished primarily by the presence of the historian R.K. Hannay’s essay on the history of the Scottish Signet, which was reprinted by the Stair Society under the editorship of Professor Hector Macqueen in 1990. The list of members is almost 100 pages longer than that in the “1890” and includes not only Writers to the Signet who took their oath in the years between the two books but also those members prior to 1594 for whom information could be recovered. An updating abstract from the Sederunt Book after 1887 was included, along with selections from the minutes of the Society’s Commissioners after 1820 and the post-1934 Society Council. These last recorded the Society’s magnificent rearguard action to protect and save John Watson’s School from the interwar government commission that had sought its closure. A list of the Society’s portraits in oil and sculpture was appended at the rear.

The Convenor of the Committee – essentially the editor and compiler – for the “1936” was Andrew Philip Melville, and the bequest of Melville’s copy, carrying his annotations, to the Society by his executors, enables the identification of the otherwise anonymous authors of the different sections of the historical introduction. The opening of the introduction up to the horizontal rule on p. xii is the work of R.K.Hannay; Melville himself then carries the text through until page xxiii. The history of the Library is the work of Kenneth Sanderson WS; Andrew Melville resumes for the account of the Society’s Charitable and Educational Trusts before James Watt’s accounts of the Widow’s Fund and the Society’s Finances bring the introduction to a close.

The “1983”

The most recent update to the list of members was published in 1983 in the form of The Register of Members of the Society to Her Majesty’s Signet. The process of updating the list had begun with the former Librarian James Christie, and it is some indication of the scale of the task that Christie’s death (that saw the task pass first to Fergus Brown WS and then to David Burns WS) took place in 1974. Nor was that the only difficulty. In 1982, the publisher, Clark Constable, went into receivership, and its successor firm, “Clark Constable 1982”, would eventually released the volume only after a certain amount of negotiation.

The introduction to the “1983” had to carry the burden of recording a series of historic endings for the Society: the cessation and replacement of the ancient procedure anent apprentices and intrants; the closure of John Watson’s School in 1975; the Library sales of 1960 and 1978-1979; the change from the Widow’s Fund to the WS Dependents’ Annuity Fund (DAF); and, in 1976, the effective end of the Society’s ancient role with the Signet itself.

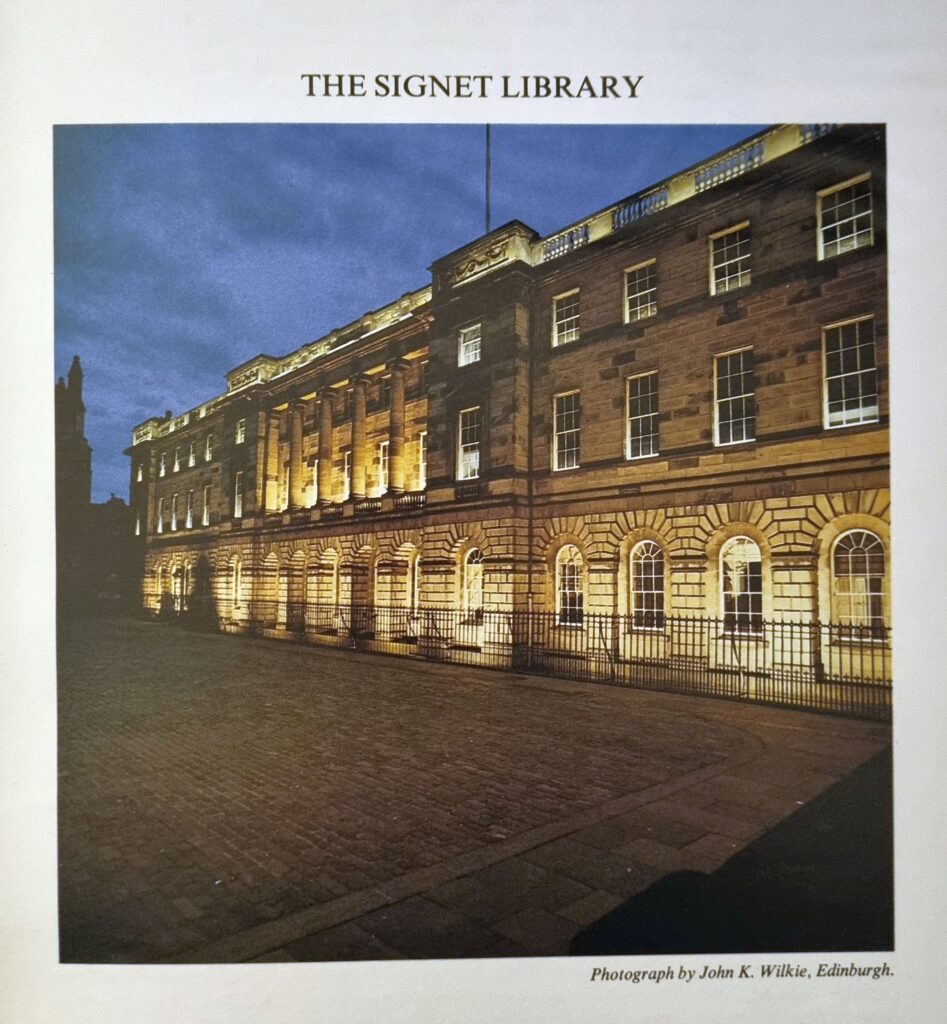

These were the amongst the challenges of the WS Society’s reorientation to the future, and the “1983” records, more cheerfully, the Society’s key role in the foundation of the Law Society of Scotland, the admission to the Society of women, the creation of John Watson’s Trust, and the wholesale restoration of the Society’s buildings and funds. The foundation of the WS Society Golf Club is here, as are the new dining societies that have joined the traditional ones in recent years. There are fresh illustrations – photographs by John Wilkie, and a beautiful pen drawing of the Upper Library lobby by Frank White.

The “1983” also reproduces a short 1970 history of the Society by Writer to the Signet and historian of Scottish droving A.R.B. Haldane, still probably the finest brief account of the Society in print.

It is unlikely that any future history of the Society will centre on a register of members. The ancient tradition by which legal knowledge was transmitted from Writer to the Signet to generations of apprentices is no more, and in a world of large cross-border legal firms, the traditional WS firm led by a pair or trio of WS partners is no longer part of the career path of most modern members of the Society. The advent of the digital age coincided with the publication of the “1983” and it has brought with it a changed attitude to privacy and the protection of information about the individual.