or: Minding your Beeswax

By Jo Hockey

Introduction : Indices: stories: unidentifIed seals

Returning to the Riddell Seals three years since studying, recording, and researching the collection, I’d like to look at other aspects of the way in which they were used. The aspects of privacy and security are often overlooked in this period (early C19) at least for those outside political, military, and royal circles – we tend to focus on the imagery displayed on the seals, and the authenticity suggested by the various heraldic devices. I’d like to discuss the ways in which literacy, the postal service, and the changing culture of privacy surrounding letter writing influenced sealing practices.

Heraldica.org describes a ‘heraldic free-for-all’ in the late C18 and early C19, in which people would display family arms without proper entitlement (the rules were very strict). They attribute this to the ending of Heraldic Visitations. Heraldic Visitations were carried out since the 1530s by the College of Arms in order to regulate the use of heraldry in England. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought about limitations of royal power (of which the Visitations were part) in favour of the landed elite of the country. English families continued to use their inherited arms but were not restricted by the rules of the College of Arms. The Lyon Court in Scotland regulated quite strictly in comparison. This situation may have contributed to a shifting emphasis on security rather than authenticity in seal use, but it could be said that the most important factors were rising literacy rates and faster/more secure postage services.

The earliest seals were beeswax (relatively easy to remove – the soft wax could be gently warmed and peeled away), only used by the literate nobility and the church, so the contents were fairly secure, with the seal acting primarily as a means of authentication. Beeswax was also believed to carry the properties of a higher authority, as bees were considered a sacred creature at this time.

With rapidly rising literacy and postal volume in the C18, seals needed to withstand covert opening, and coniferous tree resin (colophony) was added to the mixture, along with vermillion for colour, to create a harder and more brittle seal. The precise dates at which this change happened are unknown, but in Organic components in historical non-metallic seals identified using 13C-NMR spectroscopy by M. Cassar, G. V. Robins, R. A. Fletton & A. Alstin, the Medieval seals tested (up to 1553) were found to contain beeswax but no resins, while the Early Modern seals tested (post 1714) were found to contain various tree resins and mineral wax.

The Founding of the East India Company in 1600 brought shellac to Britain, primarily as an excellent varnish, but also as a valuable addition to seal recipes. Shellac gave sealing wax far more durability and crucially, brittleness, which made for a more tamper-proof seal. Shellac, the secretion of the female Lac insect found on branches of trees in the forests of India and Thailand, has been used in these countries for over 3000 years. In the early Hindu epic Mahabharata (over 2,000 years old), there is mention of lac being used in the construction of a palace (jatugriha) to house the Pandavas with the ulterior motive of destroying them by setting the palace on fire.

The Riddell Seals are entirely of the shellac based variety, but would also have contained beeswax, tree resin, turpentine, and colouring agents.

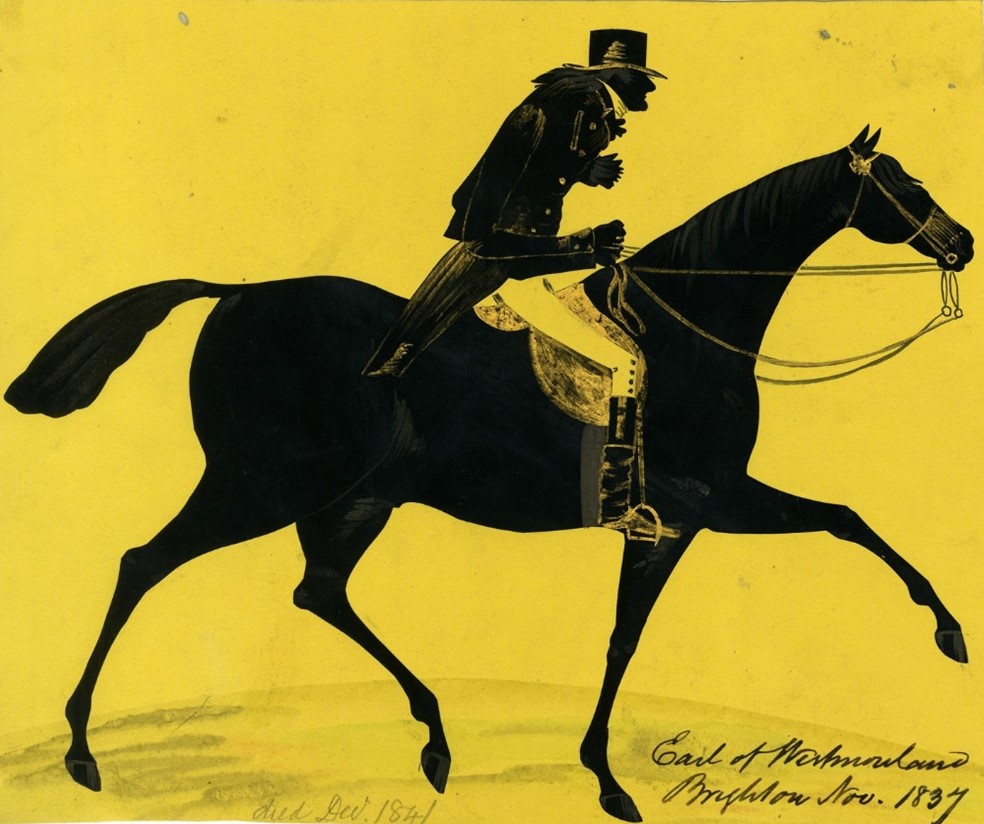

To illustrate this aspect of seal use, I’ll be focussing on three in the collection, those of Postmasters General James Graham, 3rd Duke of Montrose and John Fane, 10th Earl of Westmorland (Keeper of Privy Seal 1807-1827), and Secretary of the Post Office, Francis Freeling.

Freeling’s seal is his official one, and at this point in his career he was working to establish postal reforms. These earned him a baronetcy in 1828 and the praise of the Duke of Wellington ‘the English post office under Freeling’s management had been better administered than any post office in Europe, or in any other part of the world’. The role of Postmaster General was primarily a ministerial one, with little involvement in the practicalities of the postal system, but directing the decisions of the organisation at the highest level.

The Swan With Two Necks was the hub of much activity during the 17th and 18th centuries, serving London as a coaching, parcel and wagon office.

The Post Office at the time of the Riddell Collection was twenty years into John Palmer’s Mail Coach era (which replaced delivery by riders on horseback), and enjoying the faster, more reliable service. The Mail Coach service had been trialled in August of 1784, and by 1786 services from London to Edinburgh and to the North and West of England were established. Volume of post and revenue had increased from £196,000 in 1784 to £1 million in the early C19 and society was changing in response – businesses expanded, friendship networks developed, dependence on the service grew.

In Susan Whyman’s The Pen and the People: English Letter Writers 1660-1800, she quotes C18 letter writers. ‘The middle Post is a long one here’, observed Anne Evelyn, ‘the letters not coming in till Thursday.’ ‘I shall not disappoint’, wrote her mother, ‘of one always by Monday’s post..’ In 1748, the merchant John Tucker ordered every movement to coincide with the mail: ‘My exertions are all timed in what I call the long post between fryday night and Tuesday night, that no letters may remain unanswered that of necessity require it.’ Whyman also describes the Post Office as ‘an agent of modernisation from outside the community that unblocked and constructed a circular communications system.’

The early C19 witnessed the height of the Napoleonic Wars, with national security being quite critical. Methods of espionage developed during the French Revolution such as double agents, codebreaking and signal interception were put to use, all post being routed through London by the Mail Coaches and Packet Boats.

One particular method of espionage was the interception and copying of sensitive letters by the Post Office. This was done in secret within the organisation, and involved the identification of relevant letters, and opening, copying and resealing them without detection.

The Post Office and its predecessors had always operated some form of espionage, indeed the earliest systems for the purpose of Royal communications were carefully monitored to ensure security of information and intelligence of potential threats. In 1644 Edmund Prideaux was appointed Master of the Posts, Couriers and Messengers, establishing one of the earliest forms of the public Post Office, within which, a ‘Secret Office’ was conceived (1653), thereby formalising the function of intelligence gathering for the following 200 years. Indeed the ‘Secret Office’ worked in tandem with the ‘Deciphering Office’, which worked on breaking any coded communications.

In the 1660s Sir Samuel Morland, secretary to John Thurloe (Cromwells’ Spymaster General and Postmaster General) demonstrated various machines of his own invention to King Charles II in the Secret Office. These machines were reportedly used for unsealing, copying and resealing correspondence. J.R. Ratcliffe in ‘Samuel Morland and his calculating machines’ writes ‘Charles II’s fancy was for Morland to continue using his ‘several engines and utensils’ in the inspection of mail’. Sadly the machines were lost in the Great Fire of 1666 but many others of Morlands’ inventions have been described alongside diagrams. This article gives an excellent description of the Secret Office personnel in the C18.

By the C19, opening, copying and resealing had become a routine procedure, given the volume of letters presented to the Secret Office, and from 1798 the budget was increased to facilitate Napoleonic War surveillance work. This description of the work done in the Secret Office is taken from Michael Wheeler’s The year that Shaped the Victorian Age (Cambridge: 2022):

Then we learned the method: which was to take an impression of the seal, then carefully to break it, and afterwards, first slightly heating the surface of the wax, to press the counterfeit stamp precisely as it had been done before, so that there was no alteration of position, nor outward appearance of any kind to show that the seal had been tampered with.

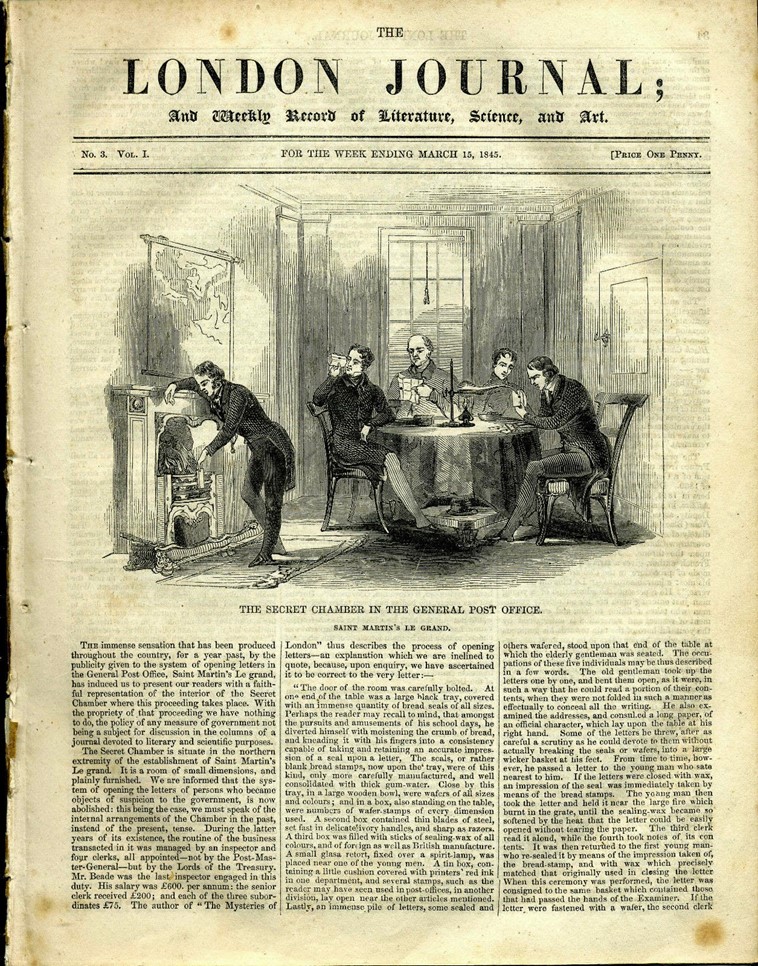

An article from The London Journal (edited by the Chartist journalist George W. M. Reynolds) in 1845 presents a depiction and description of the ‘Secret Chamber in the General Post Office’, with an interesting detail explaining the use of moistened bread to make accurate impressions and copies of the seals before they were heated and peeled away.

The issue of postal espionage came the public’s attention in 1844 during the case brought by Giuseppe Mazzini (political activist for the unification of Italy) against the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham. Mazzini was suspicious that his letters were being tampered with and had his supporters send letters to him, including tiny grains in the envelopes, which were missing on delivery. Supported by Thomas Duncombe, the radical MP for Finsbury, he petitioned Parliament, leading to extensive debates and the eventual admittance that Graham had issued a warrant for the opening and copying of his post.

A Post Office Report of 1844 was published in response to the Mazzini case, and The Danish Postal Museum describes its conclusion thus:

The report of more than 100 pages substantiated that postal espionage was at least as old as the postal service itself and it supported the Government in its recommendations’ (that the Secret Office should be abolished) In ‘The Origins of Public Secrecy in Britain’, David Vincent describes the closure of the Secret Department: ‘Two months after Mazzini’s protest had been brought to the House of Commons by the radical M.P. Thomas Duncombe, the Secret Department of the Post Office was abolished, and the official decypherer of foreign correspondence, Francis Willes, whose family had held the position since 1703, pensioned off with secret service money.

This news report from New Zealand’s Taranaki Herald (Volume LX, Issue 143905, 27 September 1912) doesn’t mention the Mazzini case, but discusses the threat of interference, and the possibility of these practices being adopted from ‘the Continent’. The description of covert letter opening and resealing is especially detailed. Being a publication read by British subjects, the editor obviously wished to emphasise the reliability of the Post Office.

The reporting of the Mazzini case was widespread, from the Post Office Report, written by a newly appointed ‘Committee of Secrecy’, to the pages of Punch Magazine, which caricatured Graham as a snake in the grass, and published ‘anti Graham’ envelopes and wafers for sealing letters. ‘The proceeding cannot be English,’ thundered The Times, ‘any more than masks, poisons, sword-sticks, secret signs and associations, and other such dark ventures. Public opinion is mighty and jealous, and does not brook to hear of public ends pursued by other than public means. It considers that treason against its public self’ (“The Origins of Public Secrecy in Britain” David Vincent

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society Vol. 1 (1991), pp. 229-248). Dunscombe argued in The House of Commons that opened letters should be marked as such and in June of 1844 Charles Dickens wrote around the seal of two letters that he posted: “It is particularly requested that if Sir James Graham should open this, he will not trouble himself to seal it again”. (Kate Lawson, “Personal Privacy, Letter Mail, and the Post Office Espionage Scandal, 1844”) Interestingly, the Secret Office’s existence also became known in 1742 after the Treasury transferred huge sums of money to the Post Office to fund surveillance activities, but the story didn’t gain public traction in the same way

The public reaction to the 1844 case can be best understood within the context of people’s expectations of privacy during the C18 and C19.

One of the earliest and most influential legal cases of relevance to private letters is Entick v Carrington [1765] EWHC KB J98, in which John Entinck, a bookseller was suspected of publishing material critical of George III in 1765. His home was searched, with much damage caused. Entinck sued for trespass, with the final ruling in his favour. Lord Camen in his closing speech declared We can safely say that there is no law in this country to justify the defendants in what they have done. If there was, it would destroy all the comforts for society, for papers are often the dearest property that a man can have.

In The Pen and the People: English Letter Writers 1660-1800 (Oxford: 2009) Susan Whyman sums up the legal status of private letters:

The levelling aspect of letter-writing had political implications. Because a personal letter was enclosed and paid for, it became private property outside the supervision of the state. As postal service became more commonplace, letters offered convenient venues for individual expression of critical views….. This arena of unrestricted discourse was as provocative to the state as any coffeehouse. By 1800, a service created to censor mail had become a private necessity and a public right.

The growing culture of domestic and personal privacy was illustrated in the central theme of the 1825 play Paul Pry by John Poole in which the central character causes trouble and ill will by constantly attempting to eavesdrop on various conversations. The character of Paul Pry was popular enough to feature (as a caricature of Graham) twenty years later, on the ‘anti Graham’ wafers seen above, and the 1844 scandal registered a further shift in privacy expectations.

It has been suggested that the introduction of The Uniform Penny Post in 1840, shortly before the Mazzini case, influenced people’s assumptions relating to postal privacy. New letter writers, previously unable to afford the postal service placed a great deal of trust in the safe arrival of their communications thanks to the huge volume of post, the introduction of the Travelling Post Office (letters transported and sorted on rail carriages) in 1830, and the innovation of pre paid stamps and envelopes.

Letters, diaries and papers represented a new ‘personal space’, with issues of personal information, ownership of ideas and innovations and political/religious dissent. While the ‘Secret Office’ was abolished, there was still a need for the state to protect the security of the nation. No doubt various means were used during the latter part of the C19 (there are several reports of interference with Irish Republic post), and in 1888 postal espionage was written into the Official Secrets Act.

Into the present day, C20/C21 letter writers have had little to worry about regarding the security of their correspondence, with notable exceptions – during WW1 and WW2 letters from soldiers were routed through the British Army Postal Service which censored any letters which may have compromised national security. Prisoners’ letters have always been carefully controlled, and current law provides for confidential communication between a prisoner and their legal adviser. In 2015 The Prisons and Probation Ombudsman (PPO) for England and Wales found many cases of prisoner’s legal communications being improperly opened, with calls to tighten up procedures. Friends and relatives of prisoners are encouraged to write personal letters on the understanding that all correspondence is checked and potentially censored.

With all sensitive communication now being delivered online, the function of letters has become focussed on administrative communication, advertising circulars and occasional cards between family and friends.