exhibition home page

Kit Baston (based on a talk given at the Signet Library, 9 January 2025)

The Donation and Donors

Three young relatives of the Polish Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski arrived in Edinburgh in 1819. They were to study at the university as part of an educational grand tour across Europe. Konstanty Zamoyski and his cousin Adam Czartoryski studied economics and humanities. Konstanty’s brother Andrzej Artur matriculated into the medical school. Krystyn Lach-Szyrma was their travelling tutor: he also matriculated to study humanities in 1820. Gothard Sobański, who was to become another donor to the Bibliotheca Polonica, joined the group, matriculating at the medical school in 1820.

Both the Czartoryski and Zamoyski families had Scottish ancestry via Lady Catherine Gordon of Huntly. Lady Catherine married the politician and lyrical poet Count Andrew Morsztyn in 1659. Adam Jerzy Czartoryski had toured England and Scotland in the 1790s and came away with a profound and lasting regard for British politics and literature. When it came time to educate the next generation, he sent his young relatives to the University of Edinburgh.

On 30 May 1821, Szyrma wrote to Macvey Napier, the Librarian of the Society of Writers to His Majesty’s Signet, with a proposal. Szyrma wrote on behalf Konstanty Zamoyski, to ‘make an offer of a certain number of books to come to one of the libraries of the city’. Zamoyski had left Edinburgh, leaving his tutor to arrange a donation of Polish books to a suitable library. Szyrma continued:

These volumes are of different descriptions and their contents various, mostly in the Polish language, partly in Latin, French, and German, almost all works of Polish authors, but a small number of them written by foreigners, and all relating to Poland, and illustrating the political, civil, and literary history of that country.

Zamoyski’s mission was to provide a resource for, ‘those who may at times wish to make Poland…the subject of their enquiry of reference, and by the collecting of scattered materials through Great Britain to obtain also some new and unknown details towards the history of his own native country’.

Szyrma revealed that the Signet Library was the Poles’ first choice because:

Having myself and my Countryman, enjoyed an admittance to the Writers Library, which we must acknowledge, has been accorded to us with a particular kindness and regard, I was unwilling to introduce this matter elsewhere, till I had previously addressed myself to you. Pray consider this as a testimony of our personal feeling.[1]

Napier called a special meeting of the Library Curators to consider the offer. He replied to Szyrma on 14 June 1821 to say that Zamoyski’s wish for the collection to be kept together in a separate place, for the library to maintain it as its property, for a separate catalogue to be kept, for the inscription ‘Bibliotheca Polonica et Lithuana’ to be added to the books, and for a book to be kept to record any future donations would all be complied with by the Writers, adding that

I feel assured that the whole body of Writers to the Signet will participate in the sentiments entertained by the Curators of their library, in regard to the valuable donation which Count Zamoyski has through you, so handsomely intimated his intention to present to it, and I beg to add, in my individual capacity of Keeper of the Library, that I shall always be ready to afford any assistance in my power to such of your countrymen as may have any literary object to pursue in this City.[2]

The Signet Library possessed books on Polish subjects before the 1820s. Its catalogue of 1805, expertly compiled by the Signet Librarian George Sandy lists, for example, The Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Northern Governments published by John Williams in London in 1777. De la Croix’s A Review of the Constitutions of the Principal States of Europe, published in London in 1792, included in its first volume, ‘Of the Constitution and division of. Rousseau’s and Abbé de Mably’s thoughts on Poland and its government appeared in their collected works. There was a collection of Polish history, letters, and descriptions edited by Longini and published in Leipzig in 1711 and William Coxe’s Travels into Poland, Russia, Sweden, and Denmark in its third edition of 1787. The second volume of Puffendorf’s An Introduction to the History of the Principal States of Europe – London, 1764 – contained a chapter called ‘Of Poland’.

It is likely that Napier showed these books to his Polish visitors. They may have been reassured by the seeds of a Polish collection already being in place at the Signet Library. Napier certainly thought so – he mentioned the visit to the curators later when they considered limiting access to their collections to outsiders. By sharing, Napier had secured a valuable addition to the library.

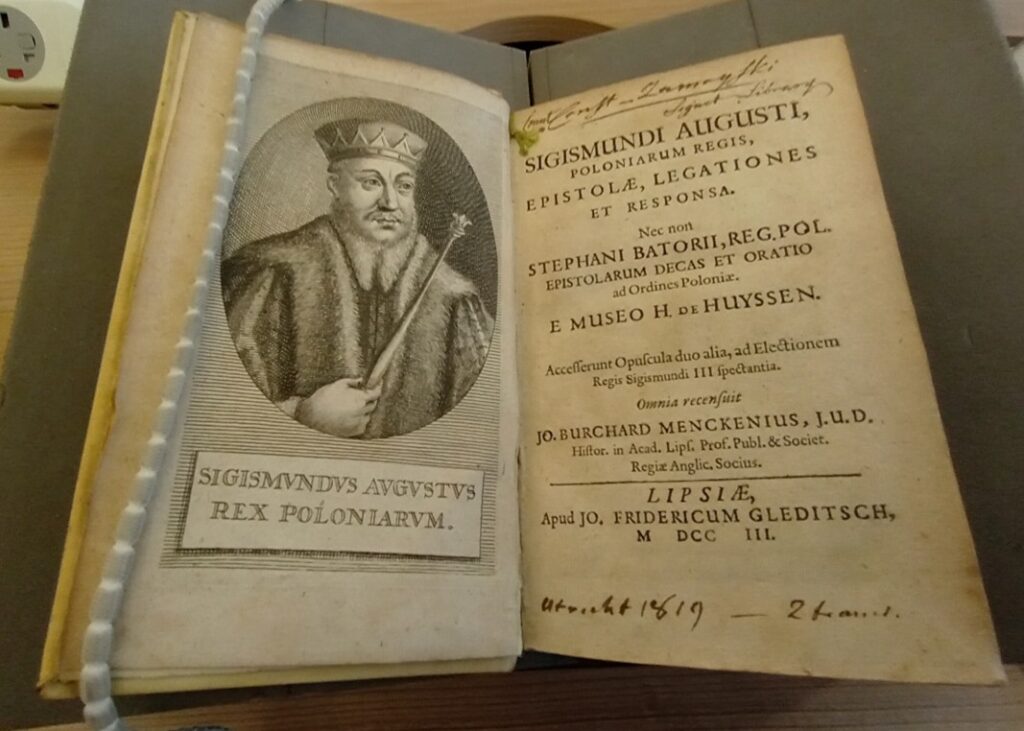

National Library of Scotland, Pol.S.25: Sigismundi Augusti, Poloniarum regis, Epistolae, Legationes et Responsa (Leipzig, 1703)

Upon his return to Poland, Szyrma published a book about his time in England and Scotland. As well has acknowledging the friendship of Napier and the Advocates Librarian David Irving, he warmly remembered two Writer to the Signet friends: Alexander Young (admitted WS in 1786) and Roger Aytoun (admitted 1790) who graciously entertained him at their country houses. Young reminded Szyrma of the proud landowners he knew in Poland when he took Szyrma on tours of his land reminding his guest of

our typical Polish landowner who will enlarge on: what his orchards bring him; what profit he has from his bees; what he gets for the wool of his sheep; how many lambs he has in the spring; what his fields and meadows yield and how he gathers it all into his barns. I was not bored in the least. I fully understood the delight felt by every landowner at the sight of the things he created.[3]

Szyrma spent four days with Roger Aytoun’s family at Muirison where he ‘enjoyed true Scottish hospitality. We talked in the evenings and spent the days walking or riding in the beautiful countryside’. The sound of an Aeolian harp charmed the visitor on Saturday evening, and he took part in a Scottish Sunday with a church service at Midcalder, where John Knox had preached. Mrs Aytoun – Joan – led the family in prayers in the evening and gave Szyrma a copy of the prayer book as a gift at the end of his visit.[4] Among the children was William Edmonstone Aytoun who would as an adult be a notable friend to Polish exiles.

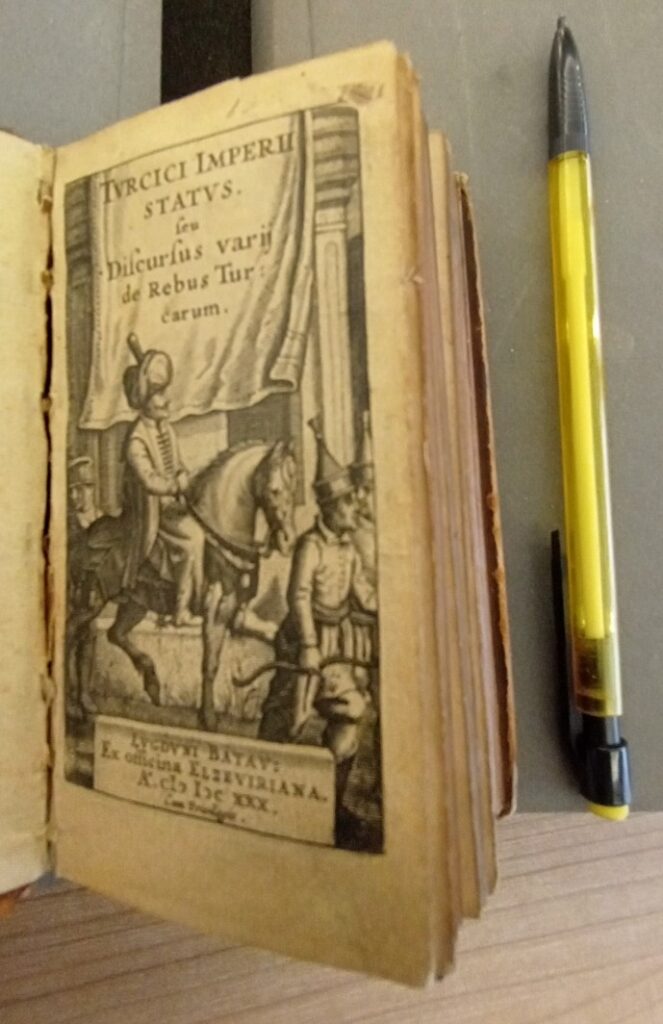

National Library of Scotland, Pol.S.1: Turcici Imperii Status, seu Discursus varij de rebus Turcarum (Leiden, 1630).

Konstanty Zamoyski, meanwhile, had been buying books on Polish subjects as he travelled through Britain with the intention of creating a reference library to deposit somewhere in the UK. He and his Czartoryski relatives came from families of book collectors who had palaces stocked with libraries back in Poland. Alongside his collecting of Polish books for British readers, he was also assembling a collection of British books for his family’s library at their famous Blue Palace Library in Warsaw.

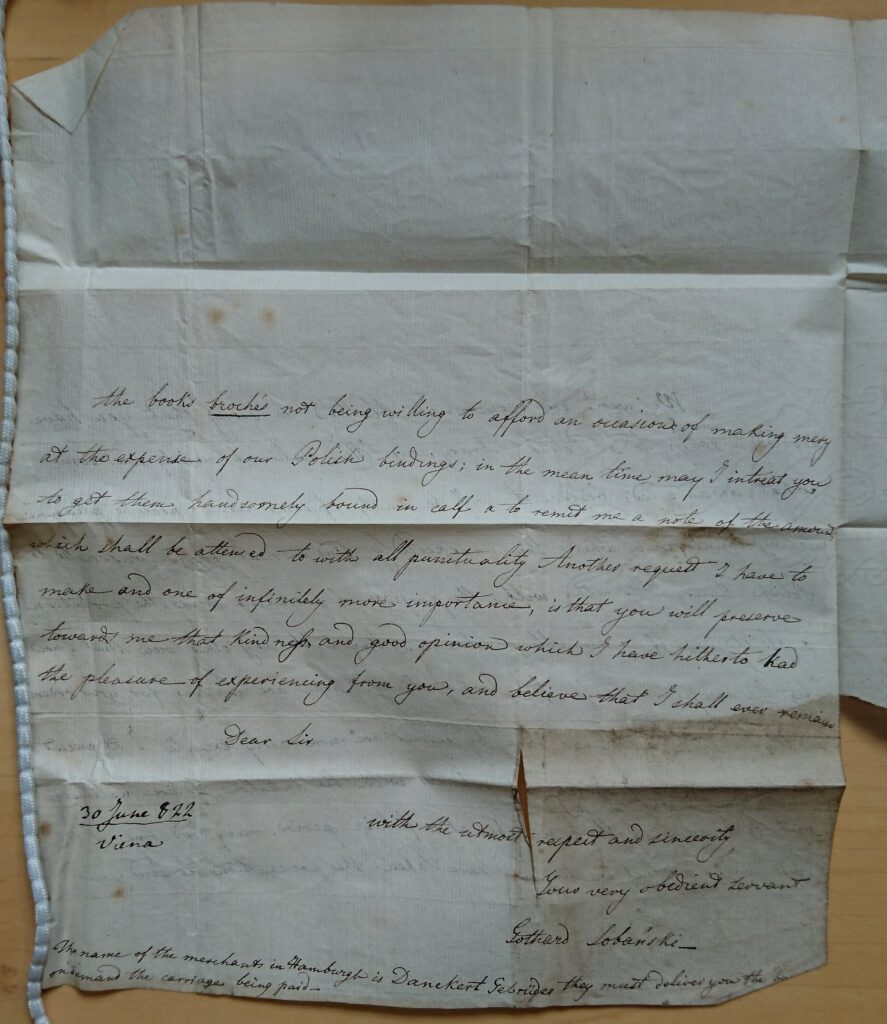

Gothard Sobański wrote to Napier about the addition of more books in 1822. These were to arrive via Hamburg with Napier ‘to get them handsomely bound in calf & to remit me a note of the amount which shall be attended to with all punctuality’. Sobański’s charming letter signs off with ‘Another request I have to make and one of infinitely more importance, is that you will preserve towards me that Kindness and good opinion which I have hitherto had the pleasure of experiencing from you’.[5] Napier reported to the Signet Library Curators on 3 July 1823 that ‘he had…received from Count Sobanski, a Collection of Books relative to the history and literature of Poland, amounting to about fifty volumes’.[6] Sobański’s donation was the second largest after Zamoyski’s.

Further donations arrived over the next few years from Prince Adam Czartoryski – it is unclear if this was Prince Adam Jerzy or his nephew Adam Constantine, a Mr Kuszeliński, Canon Surakovski of Krakow, and Count Potocki. The Bibliotheca Polonica eventually reached 123 titles in 148 volumes.

Transcription of the Register of the Bibliotheca Polonica

Dr. Kit Baston’s Survey of NLS Polish Books from the Signet Library

Visiting the Signet Library

How and when the Bibliotheca Polonica was consulted in its early years is little known. Szyrma refers to it in his Letters, Literary and Political of 1823 in ‘Letter VI’:

When ideas refuse to come we hunt for them. Such was my case – I was at a loss what to write to you. I went then to see a small collection of books relating to Poland, deposited, last year, in the Library of Writers to the Signet, by Count Zamoyski, my countryman. This view of some folios, quartos, octavos, and duodecimos, in the Polish, Latin, French, and German languages, gave me a delight equal to that of an antiquary at the sight of some old black-letter books, or some broken fragments of an Etruscan vase. My mind woke from its lethargy, and my thoughts expanded. In one instant I embraced centuries of intellectual wealth. I have now got rich in matter and in varied associations – richer than I require for a single letter.[7]

It is from Szyrma that we have one of the earliest descriptions of the Signet Library itself in its new home in Parliament Square where it had opened in 1815. In his description of Parliament House, he says.

The same building contains two Libraries: that of the Advocates and of the Writers to the Signet. The later contains many books about Polish History and Literature. Some of these are in Latin, others in French, English, German and several even in Polish….A better arranged library could not be found. Luxury and comfort are combined here. The chief hall has a double line of columns and above a gallery filled with books. On both sides in the windows there are small tables and chairs, and everybody can read and write as if in separate little rooms. The tables are immovable, made of iron and empty within, so that in winter they are used as little stoves and are heated by the air coming in from pipes under the floor.[8]

1830s Borrowing

A handful of recorded borrowings from the Bibliotheca Polonica from the 1830s appear in the donations register. Some of the dates of borrowing are unknown, such as those of Count Potocki. Polish medical student Theodore Weber, who gave his address as 18 Nelson Street, borrowed from the collection throughout 1832. This was across the street from Roger and his son William Edmonstone Aytoun’s place of business at 17 Nelson Street. The Aytouns lived around the corner at 21 Abercromby Place. William Edmonstone was a secretary for the Edinburgh Polish Association. In 1832 he published Poland, Homer, and Other Poems. He became a WS in 1835 and was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1840. He used the Nelson Street address for his fundraising activities for Polish causes.

Napoleon Feliks Żaba of No. 6 Park Street also borrowed books in 1832. He may have been working on his series of lectures on the history of Poland which he delivered at the University of Edinburgh. These appeared in print in 1834. He also edited and wrote for a periodical – The Polish Exile – from January to September 1833. Żaba was a passionate public speaker who attracted audiences across Britain on fundraising tours. Żaba moved to London and spent time as a lecturer at the University of Buenos Aires.[9]

In December 1832 there was a flurry of borrowing by WS members including Roger Aytoun, John Tweedie (admitted 1795), and William Bennett (admitted 1817). More research is needed to determine their connections with the Polish exile community. At least some of the borrowing on behalf of Poles since most of the loaned books were printed in Polish.

Polish Fancy Ball

On 16 February 1837, Edinburgh’s Assembly Rooms hosted a fund-raising ball for Polish refugees. Lady Gibson-Craig, the wife of James Gibson-Craig, WS and a patron of the event, and two of her daughters attended. The ladies’ dresses attracted the attention of the Caledonian Mercury’s reporter with Lady Gibson-Craig in black velvet, Miss Margaret Christian Gibson-Craig in sky blue satin, and Miss Joanna Gibson-Craig in pink brocade. The ‘Missess Aytoun’ also attended the ball which was ‘more numerously and fashionably attended than any other which has this season been given.’

Dinners, lectures, and subscriptions to support exiles kept the Polish cause in focus in Edinburgh. Members of the WS were deeply involved in these efforts. William Edmonstone Aytoun served as the secretary for arranging a public dinner to take place on 8 December 1835. At least a dozen WSs attended including Roger Aytoun and Gibson-Craig. William Edmonstone Aytoun gave a speech that referenced Kosciuzsko and was printed in one of the five columns that reported on the event in the Edinburgh Evening Courant for 11 December under the heading ‘Fund for the Polish Exiles’. The same newspaper reported on a ‘Public Meeting – Poland’ on 28 November 1838. James Gibson-Craig sent a letter of support and Napoleon Feliks Żaba ‘made an affecting appeal on behalf of his country’.[10]

Neglect and Rediscovery

The Bibliotheca Polonica languished during the reign of David Laing as Signet Librarian which started in 1837. The Curators’ Minutes during his decades in charge are notable for the conflict between the Curators and their Librarian who often failed to attend meetings and rarely reported on his activities. He died in 1878.

Thomas Graves Law became Signet Librarian in 1879. He worked to complete the cataloguing work that had been stagnant under his predecessor. In January 1880 he reported to the Curators that

On reaching the heading ‘Poland’ in the Catalogue I found that a donation of Polish works, and books relating to Poland had been made to the Library by Count Zamoyski sixty years ago on the condition that they should be placed together in a separate compartment of the Library and also have a separate catalogue under the title Bibliotheca Polonica. In order to comply with the second part of the agreement I propose to have a few copies struck off of the sheet of the printed catalogue which the books in question are entered, with the title ‘Bibliotheca Polonica’ and a Short note mentioning the donors gift and its occasion. This will be in the hands of the Curators very shortly.[11]

The library’s catalogue of 1882 listed the collection under a separate heading.

1940s Revival

The catastrophe of 1939-1940 brought Polish soldiers and civilians alike to Scotland in vast numbers, with Polish troops in exile guarding Scotland’s east coast. Signet Librarian Dr Charles Malcolm welcomed Polish visitors to the Signet Library to see the Bibliotheca Polonica in March 1941, when the President of the Polish Republic and his staff inspected the collection. The volumes were also ‘eagerly consulted by some of the Polish military personnel stationed in the Edinburgh area’.[6] Malcolm was active in relief efforts and the library benefitted from the connections he made. Alfred Holiński noticed that the books were not particularly well catalogued when he visited with the delegation of Polish visitors in March 1941 and he offered to identify them and improve their cataloguing.

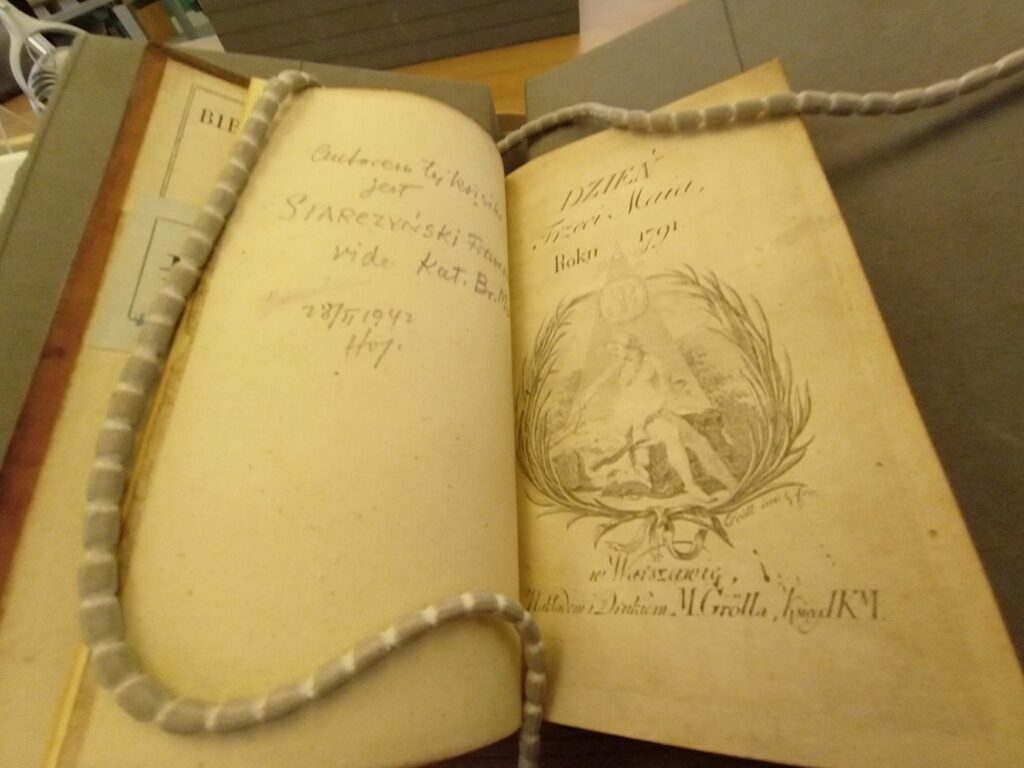

National Library of Scotland, Pol.S.21: Dzień Trzeci Maia Roku 1791 (Warsaw, 1791)

Stanisław Tyrovitz, meanwhile, created a beautiful set of architectural drawings of the Signet Library. Tyrovitz, a member of the Association of Polish Architects, worked as an artist for the National Buildings Record Scottish Council in the 1940s, documenting buildings of historic interest, including the Signet Library.

Transfer to the National Library of Scotland

The WS Society’s Annual Report for 1962 notes that ‘During the year under review further progress has been made with the disposal of books surplus to the requirements of the library’. The Librarian of the National Library of Scotland had first choice and selected fifty-three volumes of the books on science and natural history sold by auction. And ‘the collection of Polish books (143 volumes) [was] transferred to the National Library’.

Click here to review the Bibliotheca Polonica in the National Library of Scotland catalogue.

Conclusion

Libraries are so much more than the books on their shelves. This is something the young Polish visitors understood when they presented the Bibliotheca Polonica to the Signet Library in the 1820s. The books they donated were expressions of Polish culture and history, receptacles for a culture that had its traditions under threat, and time capsules.

Keeping things and looking after them, recognising their importance, is what keeps them alive. This is what Malcolm understood when he invited Polish soldiers to use the Bibliotheca Polonica. Thomas Graves Law understood it when he honoured the conditions of the gift sixty years after its arrival. Konstanty Zamoyski and Krystyn Lach-Szyrma understood it when they set the conditions for the donation and Macvey Napier and the Writers to the Signet understood it when they accepted the gift. Books can be symbols of friendship. Mrs Aytoun understood this when she gave her young Polish friend the book of prayers that she had read from when he stayed with her family.

The Bibliotheca Polonica has survived when other collections have perished. It has offered solace, consolation, pride, and hope. It is waiting for a new generation of scholars to find inspiration as Szyrma did two hundred years ago when he sat among its volumes and needed to find something to write about.

[1] Krystyn Lach-Szyrma, Letters, Literary and Political, on Poland; Comprising Observations on Russia and Other Sclavonian Nations and Tribes (Archibald Constable & Co., 1823; repr. HardPress, 2019), 147-48.

[2] Lach-Szyrma, From Charlotte Square, 25-26.

[3] Maria Danilewicz, ‘Anglo-Polish Masonica’, Polish Review, 15, no. 2 (1970): 32.

[4] Edinburgh Evening Courant (28 November 1835), 3.

[5] WS Society Library Curators’ Minutes.

[6] G. H. Ballantyne, The Signet Library and its Librarians, 1722-1972 (Scottish Literary Association, 1979), 59.

[7] WS Society Library Curators’ Minutes, vol. 1, 192-99.

[2] WS Sederunt Book, vol. VII, 99.

[8] Krystyn Lach-Szyrma, From Charlotte Square to Fingal’s Cave: Reminiscences of a Journey through Scotland, 1820-1824, ed. Mona Kedslie McLeod (Tuckwell Press, 2004), 132.

[9] Ibid., 141.

[10] Sobański’s letter and receipt for shipping from Hamburg, WS Society Archive.

[11] WS Society Library Curators’ Minutes, vol. I, 213.