CURLING AT THE SIGNET LIBRARY

A DISPLAY TO CELEBRATE THE WINTER OLYMPIC GAMES 2026

We often say at the Signet Library that the collection of Session Papers here contains all human life. In a volume of Session Papers for 1804-05 (Signet Library SP 463:20), there is a Petition relating to an ‘Action for the Recovery of a Curling Stone’ on behalf of John Valens, a member of the Westergate Curling Club of Glasgow. Valens claimed that his lost curling stone had been found in a cellar and took his case to the Glasgow Magistrates. The case eventually reached the Court of Session.

Curling has a long history and the books in this display reflect its importance in Scotland, its heritage and traditions, and its development into a sport played and viewed around the world.

This exhibition has been curated by Dr. Kit Baston who has written an additional essay on an early legal case involving curling: The Curious Case of the Missing Curling Stone.

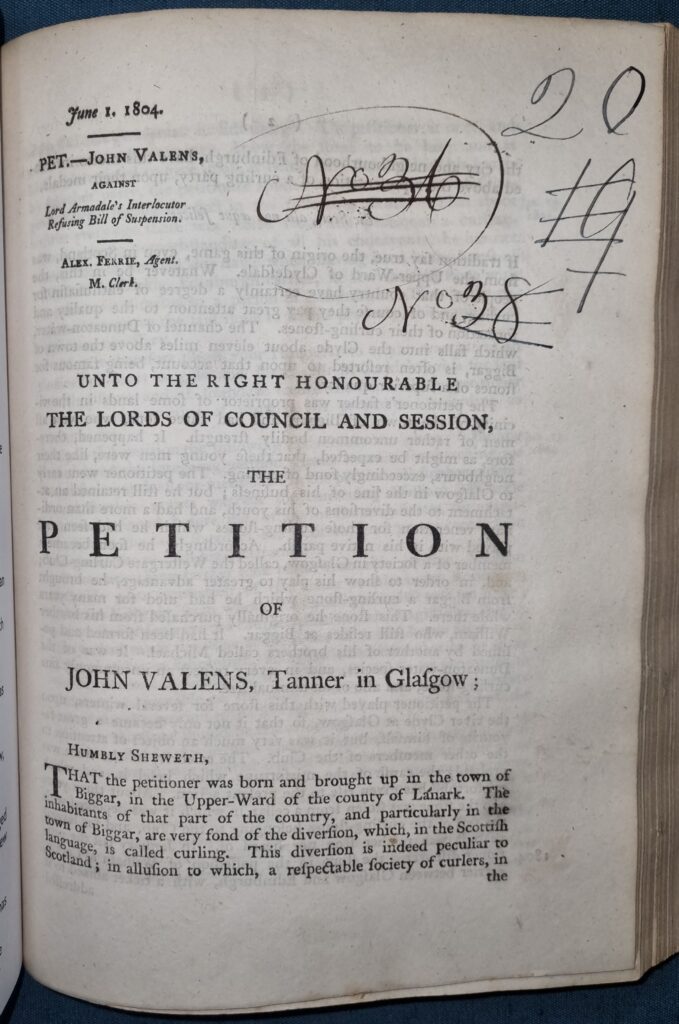

ACTION FOR THE RECOVERY OF A CURLING STONE

The Petition of John Valens, Tanner in Glasgow (1 June 1804).

John Valens, a member of the Westergate Curling Club in Glasgow, believed that his treasured curling stone had been stolen. He took his complaint to the magistrates of Glasgow when, three years after the stone disappeared, he saw it in a carrier’s yard with a label directing it to Edinburgh.

Valens appealed to the magistrates of Glasgow for justice and eventually the Court of Session. Lord Armadale judged against Valens who was to deliver the stone to the Edinburgh buyer and pay expenses. Valens disagreed and this petition claims that Armadale’s ‘interlocutor proceeds upon a mistake.’

Valens’ fellow Westergate Curling Club members rallied round with statements to support his claim that the stone was his. James Stark, mason in Glasgow, deponed that he had known both Valens and his stone for more than two decades. The stone had changed – it had a new handle, had been bored completely through, and had ‘been niched round and round…but not so much as to prevent a person from knowing it’. Charles Brown, smith in Glasgow, agreed and had seen Valens playing with the stone in his native Biggar. Daniel Ferguson, shoemaker and leather merchant in Glasgow, identified the stone as belonging to Valens and was present when he found it in the carrier’s yard. Allan Thomson, change-keeper in Glasgow, aged 60, remembered Valens playing with the stone for ten seasons. Alexander Marshall, mason in Glasgow, not only recognised the stone but had played with it himself. William Begg, mason in Glasgow, recognised the stone to the ‘best of his knowledge’ and remembered that Valens’ stone had gone missing. The witnesses acknowledged that the stone had been altered but agreed that it was the same that they knew to belong to Valens.

Valens’ opponents argued that the stone in question was entirely new. Thomas Browning, servant to Alexander Graham of Limekilns, ‘about 18 months ago…blew up a piece of rock, for the purpose of making curling-stones’. The result was ‘three rough blocks’, one of which was polished ‘to make it fit for curling’.

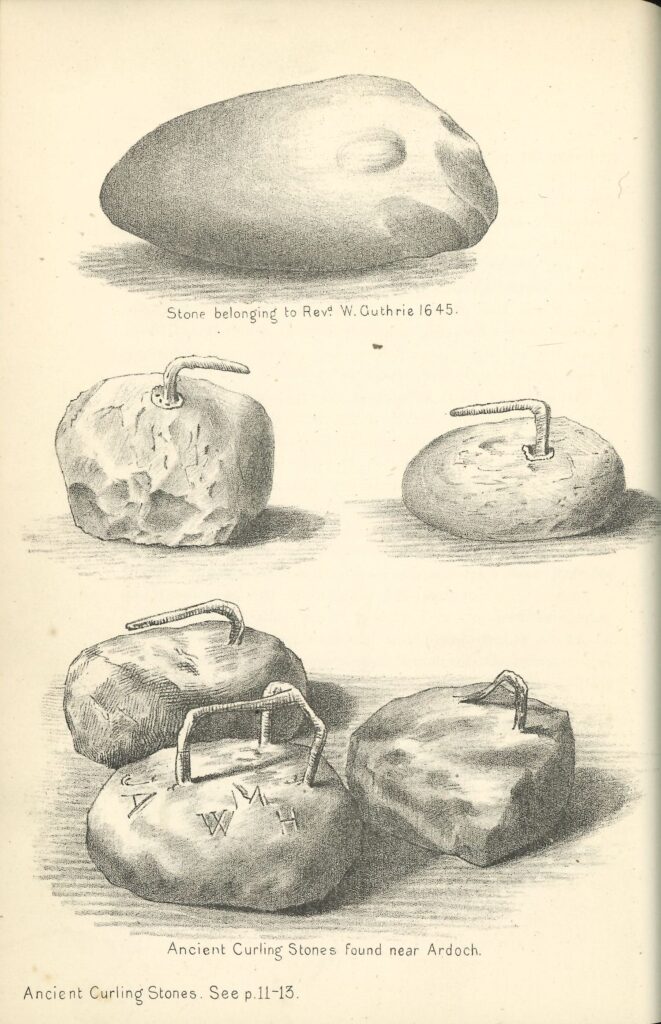

ALL SHAPES AND SIZES: ANCIENT CURLING STONES

James Taylor, Curling: The Ancient Scottish Game (Edinburgh: William Paterson, 1884).

The Ailsa Craig curling stone that we see sliding along the rink is instantly recognisable. However, until about the 1770s curling stones could be any shape or size and they could come from anywhere that suitable hard stones were found. They did not necessarily have handles; sometimes indentations for fingers and thumb were all that were required to launch the stones across the ice. They did not even have to be round: they could be shaped like tricorn hats, ducks, or frying pans. Their handles ‘were equally clumsy and inelegant, being mal-constructed resemblances of that hood-necked biped, the goose’.

Valens and his witnesses claimed that they recognised his lost and perhaps stolen curling stone because of its unique characteristics despite the alterations made to it since they had last seen it three years before.

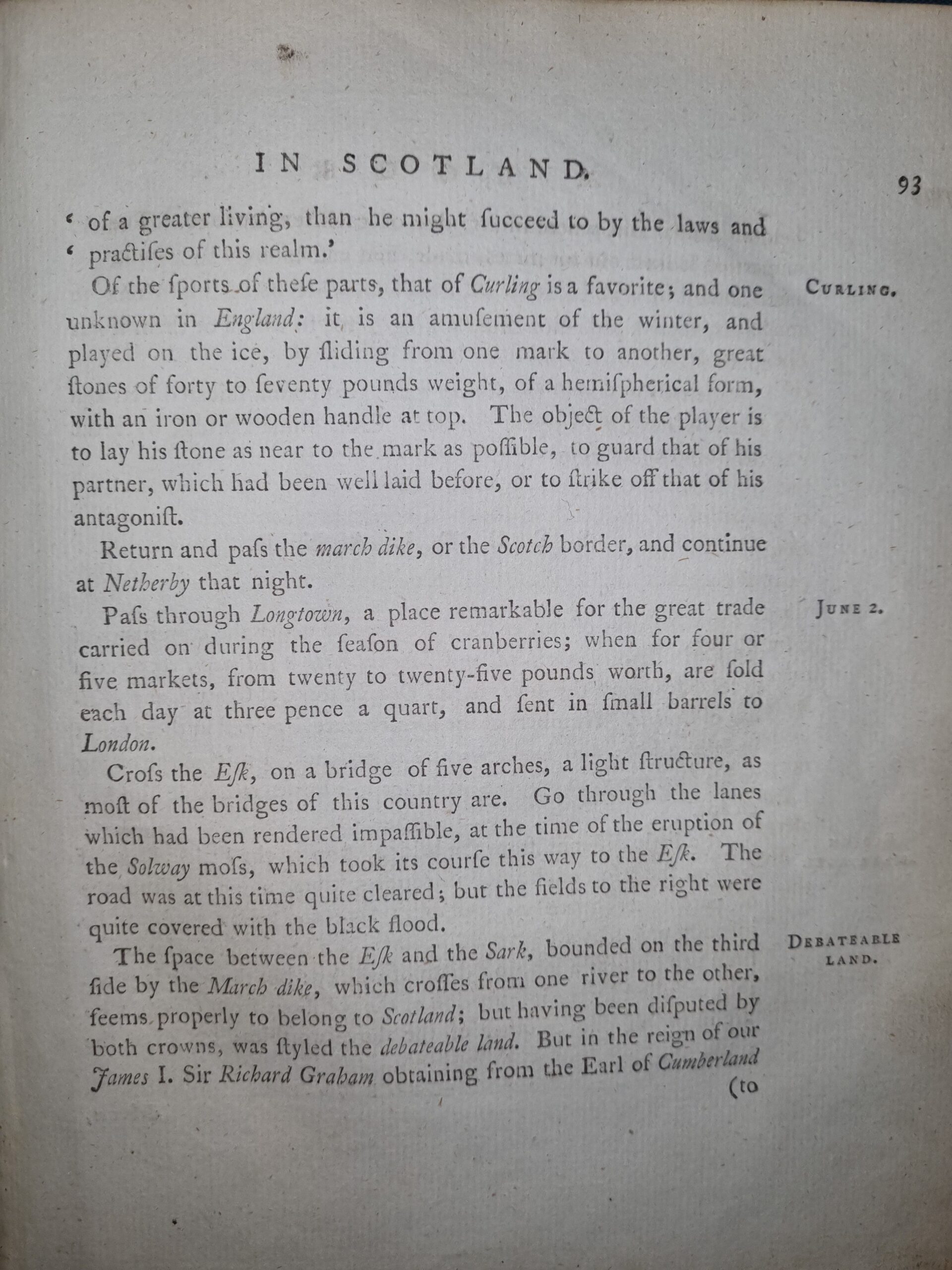

A FAVOURITE SPORT

Thomas Pennant, A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides; MDCCLXXII (London: Benjamin White, 1790).

Welsh naturalist, antiquarian, and traveller Thomas Pennant (1726-1798) toured Scotland in 1772, noticing anything of interest. Pennant noted customs and pastimes, including curling. John Valens would have started his long association with the sport at about the time of Pennant’s visit.

Thomas Gainsborough;

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales;

Of the sports of these parts, that of Curling is a favorite; and one unknown in England: it is an amusement of the winter, and played on the ice, by sliding from one mark to another, great stones of forty to seventy pounds weight, of a hemispherical form, with an iron or wooden handle at top. The object of the player is to lay his stone near to the mark as possible, to guard that of his partner, which has been well laid before, or to strike that of his antagonist (p. 93).

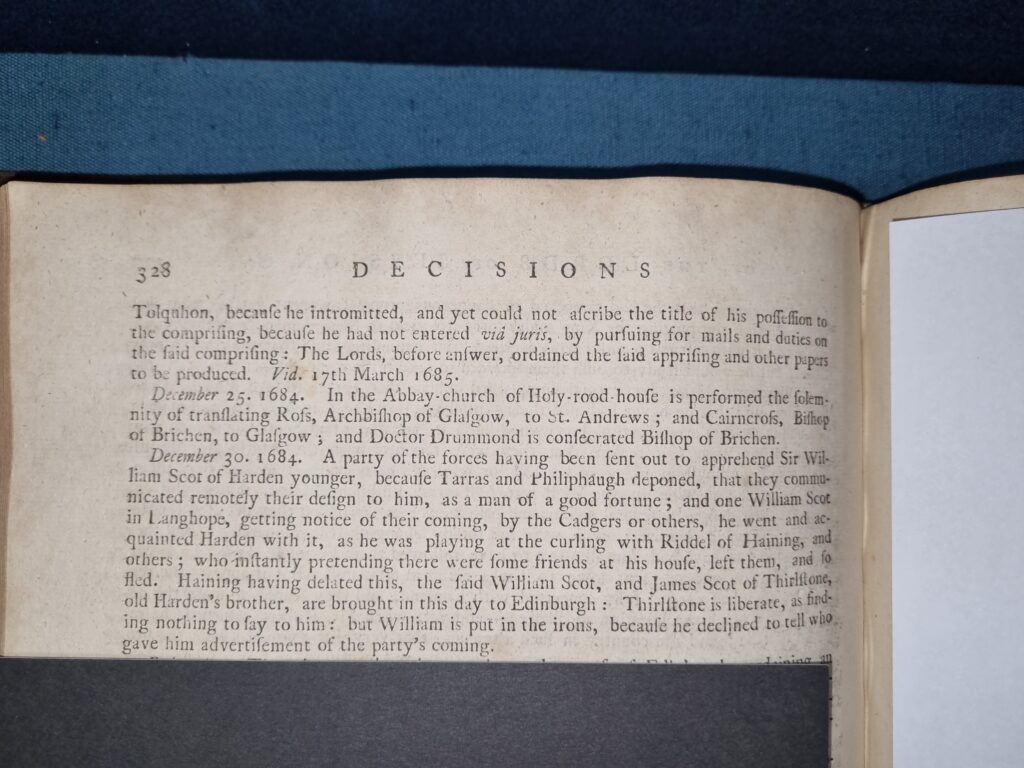

CURLING IN LEGAL HISTORY

John Lauder of Fountainhall, The Decisions of the Lords of Council and Session, from June 6th, 1678, to July30th, 1712, vol. I (Edinburgh: G. Hamilton and J. Balfour, 1759).

An early reference to curling is found in Fountainhall’s Decisions.

On 30 December 1684 Sir William Scot of Harden the younger was to be apprehended. He was tipped off ‘while he was playing at curling with Riddel of Haining, and others; who instantly pretending there were some friends at his house, left them, and so fled.’ Despite this Scot was captured, taken to Edinburgh, and ‘put in the irons, because he declined to tell how gave him advertisement of the party’s coming’.

Records of the Old Tollbooth show that Scot remained in custody throughout spring 1685, regularly petitioning for permission for visitors and for medical attention.

Scott was arrested for his involvement in the Duke of Argyll’s rebellion but pardoned and released in December 1685.

PRACTICAL CURLING

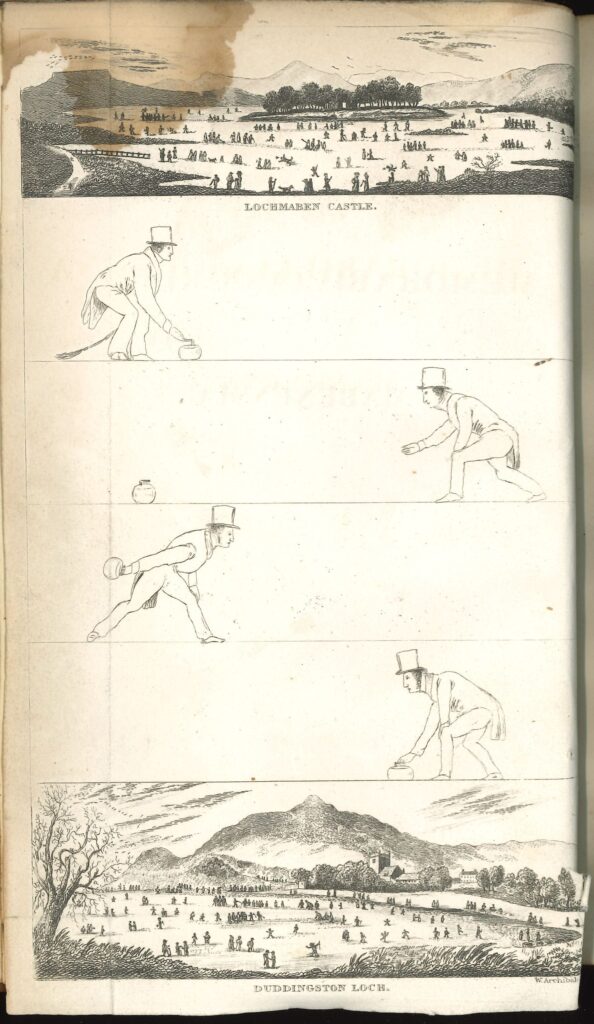

Richard Brown, Memorabilia Curliana Mabenensia (Dumfries: John Sinclair, 1830)

To curl on the ice doth greatly please,

Being a manly Scottish exercise.

[Old Pennycuik]

This volume celebrates the curlers of Lochmaben, ‘the very beau ideal of a curling station’.

It gives technical terms alongside snippets of poetry and song. It includes the Rules of Curling as set down by the Duddingston Curling Society as a model for clubs to follow as Lochmaben. There are instructions for creating artificial rinks, recommended toasts for celebrations, and rules for curling courts to resolve differences. The history of curling is covered and there are match reports for bonspiels – that is, matches between rival parishes or districts.

CURLERS IN ACTION

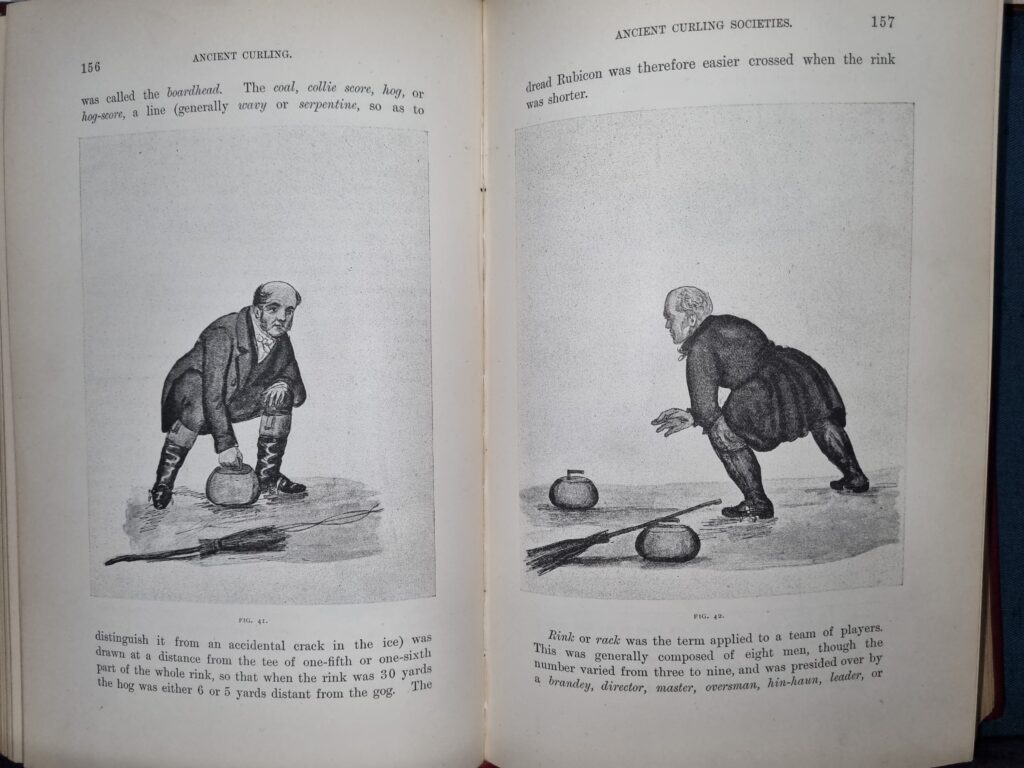

John Ker, History of Curling: Scotland’s Ain Game and Fifty Years of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club (Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1890).

These illustrations by James Drummond show two curlers from about 1842. The text notes that these ‘give a good idea of their ordinary accoutrements in the end of the last and the beginning of the present century. The kowe, cowe, or broom, without which no player is allowed to appear on the ice, is conspicuous, and there is a picturesqueness in the ancient article that we miss in our modern besom.’

A note, however, criticises the depictions, saying, ‘While the drawings are in many respects interesting, the “brethren” will detect some deficiencies which lead us to infer that the artist was not a curler’.

Sir George Harvey’s painting, reproduced at the start of the chapter, captures the moment when the stone ‘has left the hand of the player…and which “nods in conscious pride” as it moves along the howe, attended by the excited dog, who is no doubt on his master’s side, and by the faithful sweepers, has, it may be noticed, a ring-handle, and is rather more antique in appearance than those which are at rest around the tee.’

THE HISTORY OF CURLING

An Account of the Game of Curling with Songs for the Canon-Mills Curling Club (Edinburgh, 1882).

The Reverend John Ramsay’s An Account of the Game of Curling is the first history of the sport. Printed in 1811, ‘by a Member of the Duddingston Curling Society’, it was by 1882 scarce. This reprint is combined with Songs for the Curling Club held at Canon-Mills. By a Member which was originally published in Edinburgh in 1792.

Both publications reflect the enduring popularity of curling in and around Edinburgh and the traditions that grew up around it.

DOGS, UMBRELLAS, AND CIGARS: WHAT NOT TO BRING TO THE RINK

John Gordon Grant, The Complete Curler being the History and Practice of the Game of Curling (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1914).

In addition to providing a history of curling, this book contains useful information on the ‘Don’t’s of playing the game’:

- ‘Don’t swear – if you can help it; and don’t lose your temper.’

- ‘Don’t smoke cigars or cigarettes on the pond.’ … If we must smoke when curling – and I am afraid that some of us must – let us smoke our briar-root or clay. If, however, we do try an occasional cigar (or that other apology for a smoke, a cigarette), sooner or later the ash will fall on the ice; and cigar ash on the rink is diabolical, especially when it is thawing….Many a well-played stone has been totally wrecked by a lucifer lurking half-way up the rink.’

- ‘Don’t bring sand or earth on to the ice with your boots – it is far worth than tobacco ash.’ In other words, ‘Wipe your feet on the mat’ before going on to the pond.

- ‘Don’t borrow stones, but keep a pair of your own’ – after you have learnt to play.

- ‘Don’t come on to the pond without a broom, besom, or cowe.’

- ‘Don’t bring dogs on the pond.’… ‘The dog on the pond is…an unmitigated nuisance. He is in everybody’s way. His favourite performance is to walk slowly across the rink just as you are delivering your stone. This he does so often that you would almost think he was doing it ‘of malice prepense.’ His owner shouts to him, and others wave their brooms at him (and also shout): and off he goes. And in another minute or two he is there again. It is a delicate point whether it is the dog or his master that ought to be shot. Therefore leave your dog at home. Also your umbrella: for no curler can retain his dignity on the ice with a “gamp” in his hand.

- ‘Don’t boast of your skill as a player, and don’t brag of the medals and other equally useless things you have won – and are going to win.’

- ‘Don’t object to the place allotted to you in the rink by the skip.’ Whatever that place may be, cheerfully do you level best to win the game.

- ‘Don’t forget to learn the rules.’

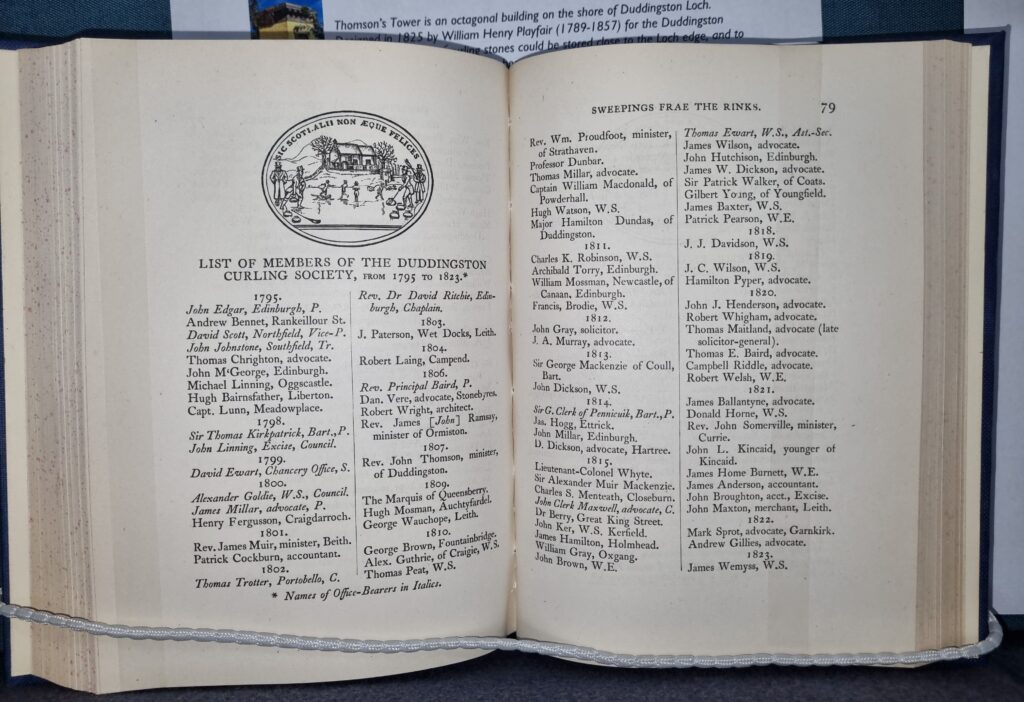

The Channel-Stane or Sweepings from the Rinks (Edinburgh: Richard Cameron, 1883)

The Duddingston Curling Society, founded in 1795, was one of the most influential in the development of the sport. Its rules of 1804 were adopted by clubs across Scotland and then farther afield as curling became an international sport.

Lawyers, known for their sociability, were unsurprisingly among the society’s earliest members. This list of Members includes many Writers to the Signet who played the game with ministers, authors (James Hogg joined in 1814), merchants, accountants, advocates, and Lords of Session.

| 1800 | 1815 | 1823 |

| Alexander Goldie | John Ker | James Wemyss |

| Thomas Ewart | Edward Hoggan | |

| 1810 | James Baxter | James Lang |

| Alexander Guthrie of Craigie | Thomas Patton | |

| Thomas Peat | 1818 | Thomas Innes |

| Hugh Watson | J. J. Davidson | David Greig |

| Robert Sandilands | ||

| 1811 | 1819 | James M. Melville |

| Charles K. Robinson | J. C. Wilson | Andrew Clason |

| Francis Brodie | James Singers | |

| 1821 | R. Sym Wilson | |

| 1813 | David Horne | Francis Wilson |

| John Dickson | Roger Aytoun | |

| James Dunlop | ||

| George Dunlop | ||

| R. W. Niven | ||

| C. C. Stewart |

Thomson’s Tower is an octagonal building on the shore of Duddingston Loch. Designed in 1825 by William Henry Playfair (1789-1857) for the Duddingston Curling Society so that curling stones could be stored close to the Loch edge, and to provide a meeting space for members in the upper room.